Did you start learning to code or draw first? Did it happen simultaneously? How did you get into it?

I started to learn programming auto-didactically when I was 8 years old and my older brother Urs and I received an old Commodore VIC-20 from our cousin, with a tape player for data (floppy discs were very just becoming fashionable, and hard-drives were a thing of the future at that time). We were naturally fascinated by the games first. But quickly the possibility to actually tell this machine what to do became really appealing to me, because the device came with a manual for programming it in BASIC, and even loading a game actually involved typing two BASIC commands on the command line. Later on Urs received a C-64, and I was using it more and more to write programs.

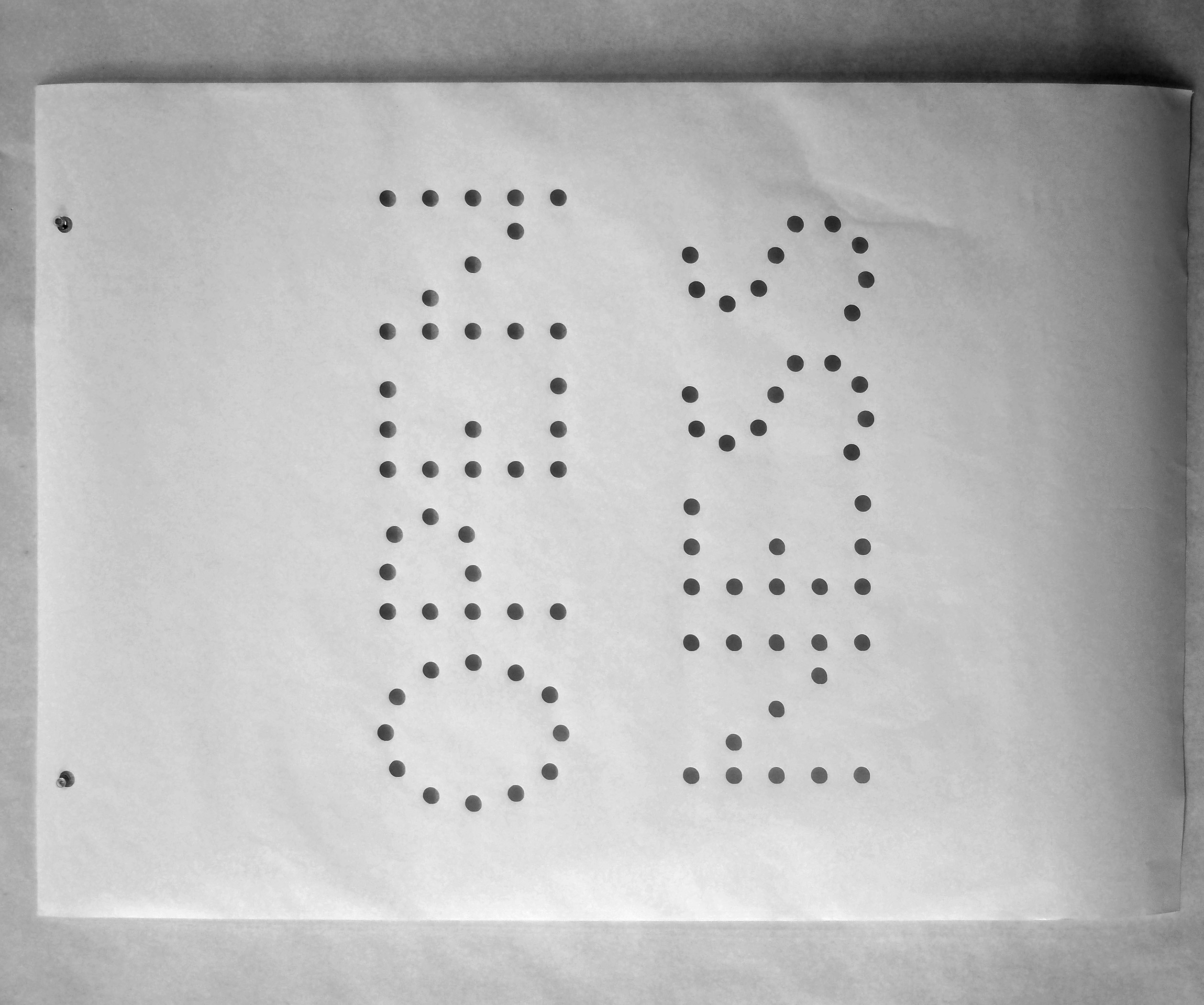

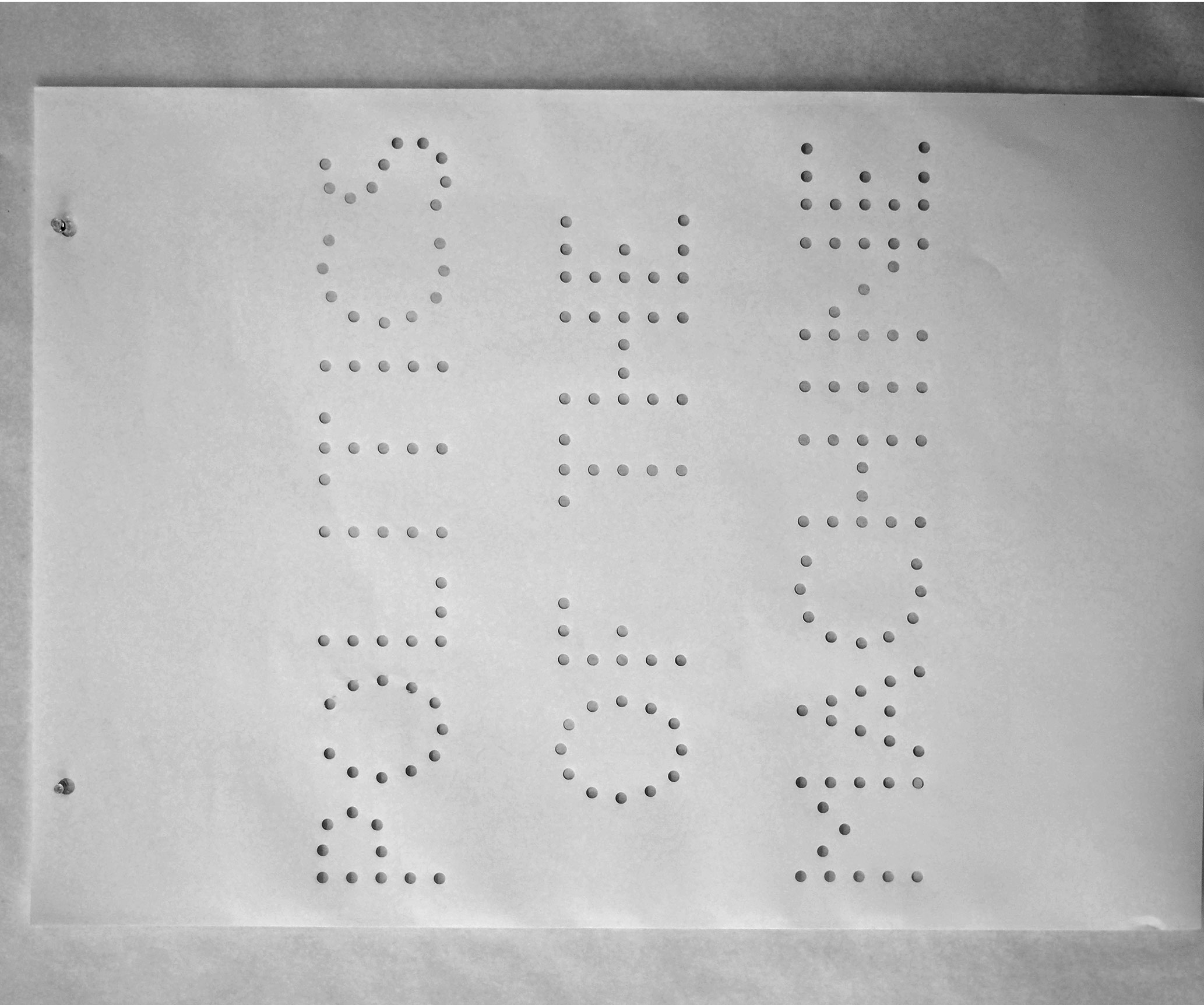

At one point we received a dot-matrix needle printer, and a tiny pen plotter, and both could be directly programmed in BASIC. I think this experience had a big impact on both of us, in different ways, as the notion to create our own tools and processes that we have full control over became a component in both our careers as designers later on. But while Urs was always more on the visual side, I was the one heading towards science and math first, before deciding to embark on an adventure in combining the two fields. What fueled this decision was the realization that I was always using visual metaphors to understand abstract mathematical concepts, and that I was attracted by the idea of abstract craft in computer programming.

Could you talk about your relationship to code? Do you still write the code for your projects or do you collaborate with a developer? Do the mechanics and constraints of code inform your process in a fluid way or do you start with the concept in mind and try to execute it however the project demands?

My relationship to code is maybe similar to that of a craftsman to his craft. I see it as a way to form abstract material, and I constantly read on new ways of building things using code. I have a strong sense of aesthetics in code, and perhaps the project where I follow that urge the most is Paper.js, as it is an open-source project with a growing audience that understands this. I believe that code can be beautiful or even poetic, and I prefer flexible, dynamic and expressive languages such as JavaScript or Ruby over languages that force me to think like an accountant (e.g. Java). So yes, I still mostly write my own code, but I really like collaborating with other people on programming projects, for example with Jonathan Puckey first on Scritpgorapher.org, and now on Paper.js. I’ve also worked with other programmers on commercial projects and enjoyed that process. It made me understand how much coding can be an activity of self-expression, with each person’s coding style being unique.

As for the influence of programming on other aspects of my practice or even my life, I certainly think there is one. Programming encourages thinking in abstract terms of systems and interconnections. Being able to do so fluently certainly shapes the way one thinks about other things. Almost all my physical artworks for example have the nature of tools, platforms and structures for production, similar to the way one would shape a programming library or framework as a platform to be of use to others.

In each of your pieces, what constitutes the final work? Do you consider Hector or Viktor, the machines themselves, to be the work of art, or is it the drawing they create? Or, could it be the ‘performance’ of the machines creating the final outputs?

I think all these aspects are part of what the final work consists of. This is partly why I give these machine names, because it suggests their perception as entities with their own character (the performance) and their own body of work (the final outputs). So the work is the combination of the proposal of the machine / process as a way to make something (mostly an image) plus the moment of the output’s creation, plus the output (if there is one to stay).

Can you talk about the disconnect between a smooth vector line and a stepper motor drawing that line with chalk? Is there something about the medium and the translation through media that adds value to the final output?

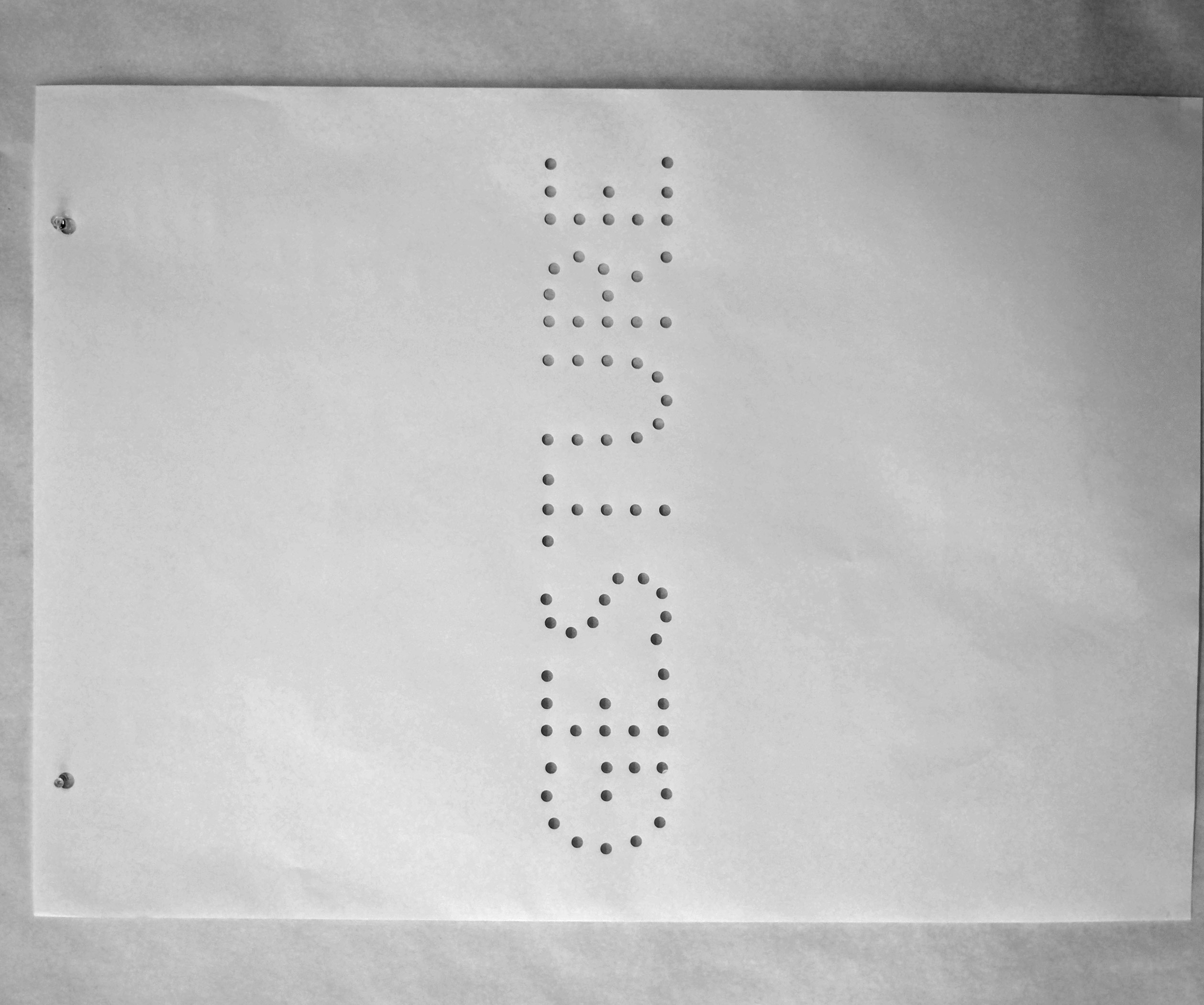

Yes that disconnect is very much at the core of many of my works. I’m fascinated by the mathematical, abstract nature of vector graphics, as it uses mathematics to form and describe concrete shapes. Rafael Rozendaal and I are talking about this to great length in the conversation published here. I was also discussing the same topic a lot with David Reinfurt when he was working on his contribution to Moving Picture Show, called Letter & Spirit, of which you can see a sequence at the top right of this video here. I think it’s best to directly quote from there: “ This distinction between the abstract mathematical formulation of geometric shapes, and their realization into concrete, physical forms is pretty much at the core of my fascination (or shall I say obsession?) with vector graphics. The shift is always there, whether it is illuminated pixels being turned on or off, a mark-making tool being moved by motors, or a laser beam being guided by electronically-moved mirrors, burning a line permanently into a physical surface. What it boils down to is the difference between the abstract idea behind something on one hand, and its concrete form when it becomes reality. Plato’s theory of forms comes to mind, with its ideal or archetypal forms that stand behind and define the concrete, physical things. ”

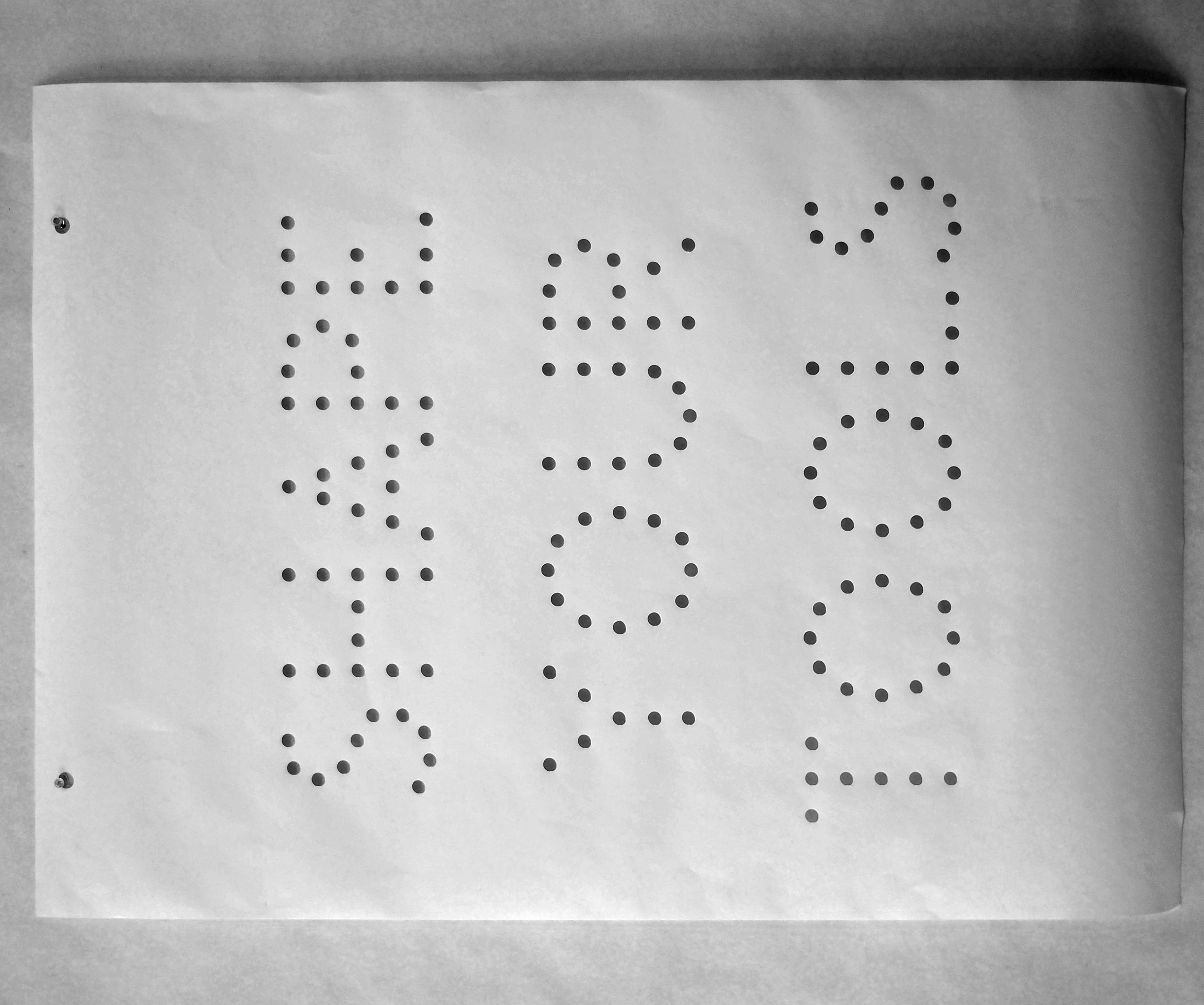

I’m very interested in the way your work highlights the intersection of alternate forms of communication: computers interpreting human language, mechanical servos interpreting code, humans interpreting coded objects such as punch cards … Are you intentionally trying to put these things in conflict with each other? If so what appeals to you about this kind of tension?

I am interested in the idea of gestures. A machine making something always does so with its own characteristic gesture, wether the nature of its character was designed in an intentional way or not. Each industrial device, each piece of software has its own gestures, and in my work I test these for their poetic potential, and I celebrate that.

I’ve noticed that works like Hektor, Empty Words, Moving Picture Show, are all very open about revealing the mechanisms of the tools themselves. Is this an intentional choice, and if so why do you think it’s important to do so?

Yes, that’s very intentional. It has partly to do with this interest in gestures and the urge to unveil and disclose them, but it goes further: It is really important to me that the technology I use is displayed as something transparent and open, not magical, closed and seeming superior. This fascination goes straight back to the openness that I encountered when exploring the Commodore computers in the 80ies. They were open structures, almost begging to be tinkered with, very unlike today’s shiny touch sensitive glass surfaces of our smartphones and tablet computers, that pretend that the technology is not there, and offer no interface to directly programming these devices. Giving my works this transparency and openness helps people appreciate them rather than being controlled or frightened by them. And it is the very same motivations that cause me to engage in the creation of open-source software that is built to teach programming to designers, such as Scriptographer.org or Paper.js

Your use of the Speed-I-Jet seems to really emphasize the idea of instant reproducibility, both of content and of form. What draws you to this act of repetition? Is it just a byproduct of working with machines?

It’s the same interest in gestures again. I love what happens with the Speed-I-Jet when someone uses it to print for the first time. You hold it like a pen, and move it on a line, but you are not necessarily the author of the letters that come out of it, yet you give it a personal touch, by the way you move and control the printing head. The boundaries of authorship get blurred as you become part of the printing process, basically replacing the parts of the inkjet printers that take care of the x-y motion. It’s this beautiful combination between a human gesture and a machine gesture that Alex Rich and I felt was worth celebrating with a modest piece of work.

Some of my first exposure to scripting was through Scriptographer. When you announced that you would no longer release new versions because of Adobe’s attitude towards API’s, I felt like the design community lost a valuable tool. Were there other considerations to ending development on Scriptographer besides Adobe’s stance? Philosophically would you rather build a tool for an open environment than a widely used closed one?

It was really hard to come to this conclusion, and I’ve been sitting on the fence with it for years. But with each new release of Illustrator, rather than spending time on new features and ideas I just found myself patching and fixing newly introduced issues and incompatibilities. As a result, all the fun was disappearing and I didn’t enjoy working on the project anymore. And while I initially built it to run projects like Hektor, Viktor and Rita, and to teach programming to visually thinking people, I had less and less time to actually make things with it by myself.

But I knew that the core idea was right, and that this kind of environment is exactly what it takes to teach scripting in a design oriented context, so I felt it was best to move on and put the energy into Paper.js instead. I am just about to start working on a graphic user interface for Paper.js that replicates some of what people came to love in Scriptographer, and I am excited to be able to use this for more teaching soon. I think eventually it will get to a point where we won’t have to look back anymore, because the new solutions will offer more openness and freedom than a corporately encapsulated solution ever would.

Now that the digital and mechanical tools you incorporate in your work (i.e. the die-cutting machine in Empty Words, or even a browser) are becoming proprietary objects, are the politics of the companies that create these tools something you consider when creating your work? Just like the shape of a brush creates different forms, do you think the intentions or desires of the companies behind these tools shape an artist/designer’s final output?

Yes of course each tool has an impact on its user. The quote “We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us” comes to mind, which gets wrongly attributed to Marshall McLuhan, while it was actually by Father John Culkin, SJ, a Professor of Communication at Fordham University in New York and friend of McLuhan. With the gently changed vinyl cutting machine, the politics of the actual machine indeed played a role (not a die-cutting machine, which is another process). Alex and I thought of vinyl labeling as a rather uninteresting default way of putting letters on a wall, similar to the use of color laser printers, or 3D printing, which is now all the rage whenever somebody wants to make a physical object. It felt good to give such a machine, which one could argue has killed the sign painter, a new more friendly meaning.

There is a similar context to Moving Picture Show, which only became feasible through the extinction of 35mm film as an actively used medium for film projection. The laser subtitling machinery used to make these films would never have been available before that, and will soon disappear completely. The moment was just right to make a piece of work that speaks of a transition caused by technological advance, completely transforming a whole field of visual production.